Short Tunes with Long Tails

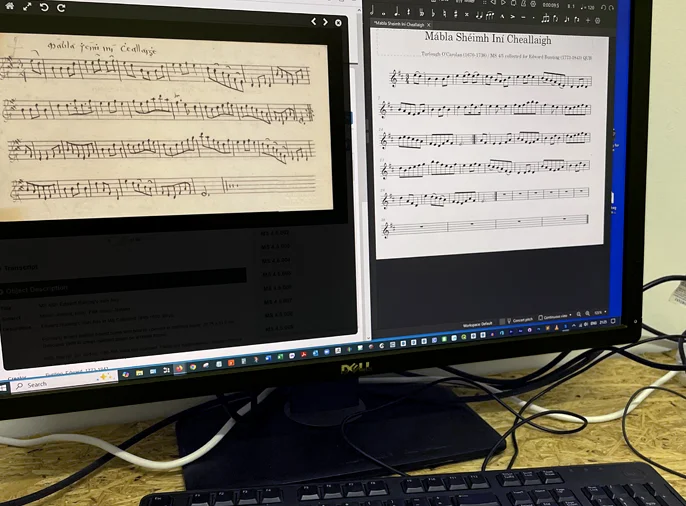

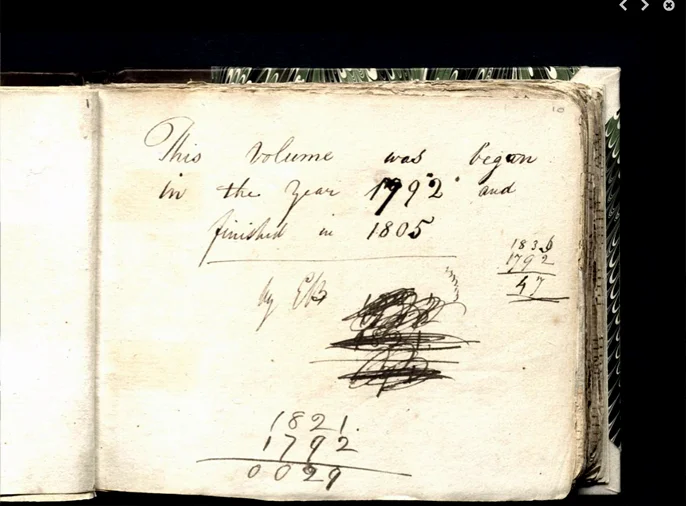

Edward Bunting, in the Preface to the 1809 volume A General Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, comments on the phenomena of oral transmission and how music is passed from performer to performer.

The editor was appointed to note down the airs played on the occasion, and cautioned against adding a single note to old melodies, which would seem to have passed, in their present state, through a long succession of ages. Though collected from parts distant from each other, and taught by different masters, the harpers always played them in the same keys, and without variation in any essential passage or note.Overlooking his wishful bias in making claims for the tunes to have

passed through a long succession of ages, it is still interesting to observe that the act of his own notation, subscribes to an indexical relationship that comes out of the Peircean trichotomy of signs.

Charles Sanders Peirce was an American philosopher and scientist who developed a theory of signs according to how the category denotes its subject. One his best known topologies is that of icon, index and symbol - icon denotes through likeness; index through causal connection to its referent; and symbol is arbitrarily assigned so must be learned by association. To explain indexicality we can draw on the method of making photographs, a technique Peirce used in his own astronomy observations:

We see things because light reflects off their surface and enters our eyes. We cannot see in darkness, but when an object is illuminated, it absorbs some of the wavelengths of light and reflects the rest of it, travelling in straight lines in all directions. The wavelengths of the reflected light determine what colour the object appears to the human eye. How a camera obscura (a precursor to the camera) functions is similar to the way light enters our eyes. With a small enough opening on one side of the box, rays that travel directly from the scene outside will get through and form an image on the surface opposite. When light-sensitive film or paper is placed on this screen, the varying densities of light and specific colour wavelengths that reflect off the object and enter the box will affect the light-sensitive material to form the latent image.

A photograph is an index because it is a fact that it is known to be the effect of the radiations from the object

. When a negative is imprinted with an image, a corresponding scene must have existed in the physical world. The imprint of rays are proof

that the original object/the source existed. This idea of indexicality – that an object indirectly bears witness to the presence of another – is a formidable concept when thinking about sources of historical research.

We can think of this image of music notation, that we know to have been made directly from the live performance of a harper, to be an index, in that arrangement of marks on the page, were caused, by an indirect but present source. For Peirce, the index (in this case the image of notation) points to a physical process that led to its creation, but it cannot tell us much detail about that process. We cannot use it to faithfully recreate all that Bunting heard. It will require interpretation. That is true too of the photo negative. It may capture the scene exactly as the rays of light evidence it to have been, but it does not tell us of what is just outside the frame, that could contextually change the meaning of what the image represents. We have to consider the subtleties of sources, of what is said and what is not said.